Report Analysis: The RSF World Press Freedom Index 2025

Global press freedoms under threat from both political and economic pressures

Reporters Without Borders (Reporters Sans Frontières, or RSF) released it’s Press Freedom Index this month, and in their own words:

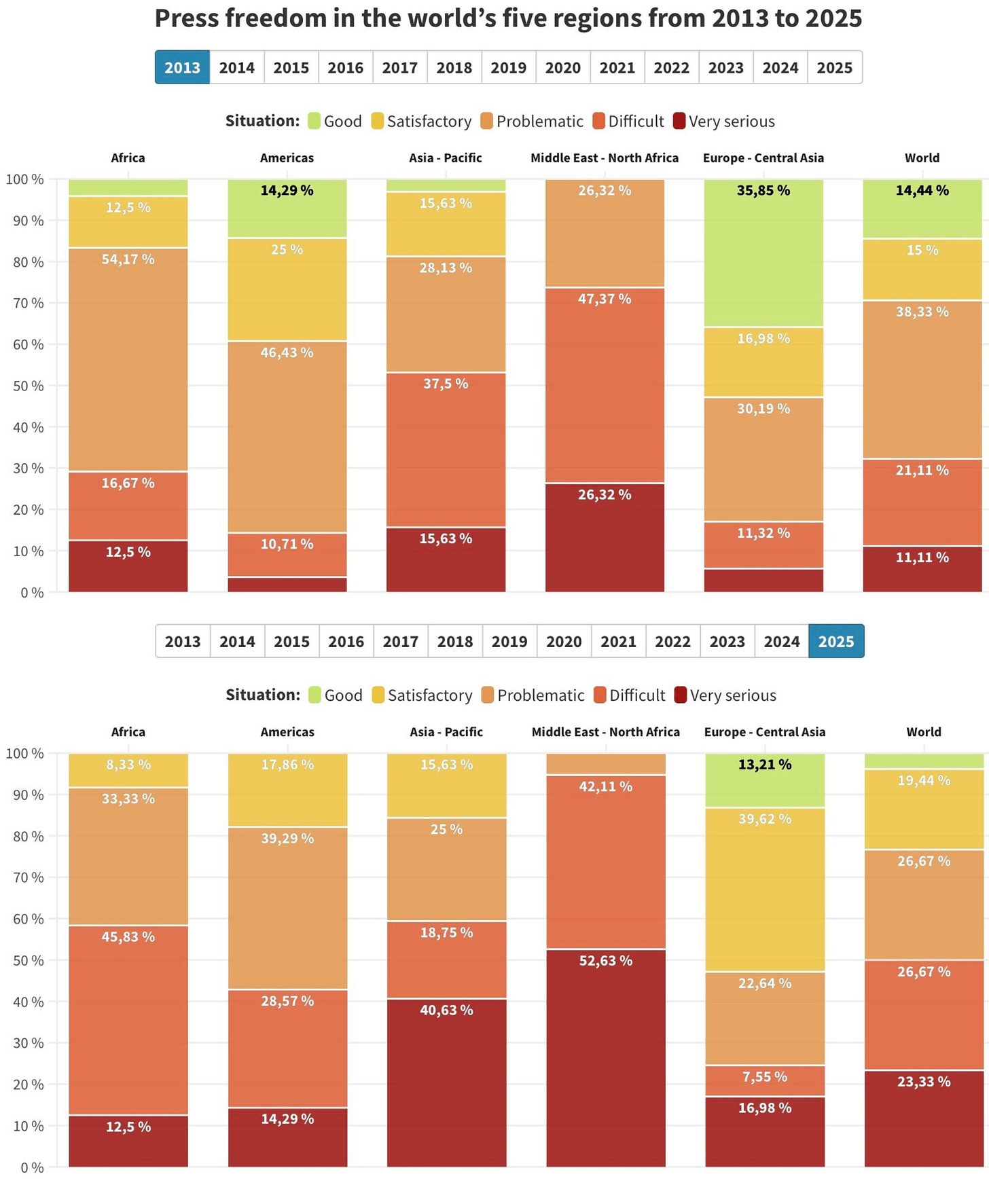

The economic indicator on the RSF World Press Freedom Index now stands at an unprecedented, critical low as its decline continued in 2025. As a result, the global state of press freedom is now classified as a “difficult situation” for the first time in the history of the Index.

In countries where press freedoms were already scant, the greatest hits are still being blasted out: censorship, laws curtailing free speech, the harassment of journalists by state actors, threats of libel suits, government influence or control over state or mainstream media outlets, etc etc.

But another thing that’s starting to bite is economic pressure on the media, an industry already struggling for financial sustainability.

As with most rights groups, RSF isn’t thrilled about the re-election of Donald Trump in the US (honestly, I was surprised that the US’s ranking only dropped by two places). The report characterises the Trump administration as a ‘leader of the economic depression’.

“President Donald Trump’s second term has already intensified this trend as false economic pretexts are used to bring the press into line. This led to the abrupt end to funding for the US Agency for Global Media (USAGM), which affected several newsrooms — including Voice of America and Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty — and, as a result, over 400 million citizens worldwide were suddenly deprived of access to reliable information. Similarly, the freeze on funding for the US Agency for International Development (USAID) halted US international aid, throwing hundreds of news outlets into a critical state of economic instability and forcing some to shut down.”

It’s common to hear about news outlets closing down, filing for bankruptcy or cutting staff. With US-initiated trade wars resulting in figurative belt-tightening around the globe, outlets that were already struggling are going to have even less resources to draw on.

The Downward Spiral

In the Asia-Pacific, the erosion of media freedoms is apparent.

The past 12 years have seen improvements in some places, but this is weighed against numerous other countries sliding into the ‘very serious’ ranking — in other words, hitting close to the bottom rung. Add the online spread of disinformation and misinformation, reporters being poorly paid and overworked, media groups being bought up by rich individuals who may censor what is being published, and unfortunately and it looks like this trend is set to continue.

In the press freedom index, the RSF scoring for each country is based on five metrics: Political (how much a country’s media is supported by domestic political entities), Economic (financial considerations), Legislative (the sort of legal protections journalists have — or lack thereof), Sociocultural (in RSF’s words, the “impact of social and cultural constraints […] that obstruct journalistic freedom and encourage self-censorship”), and Security (how safe it is to work as a journalist). These are then tallied together for the Global Score for each country.

But sometimes a country’s score can be a bit out of whack with its ranking, and improvements in a country’s ranking might not necessarily reflect improvements on the ground.

So let’s go through some of the highlights (and lowlights) in the Asia-Pacific. (I’d love to do a run down of these countries like an NFL draft announcement with thrashing guitar music and obnoxious graphics, but unfortunately I can’t try and justify such budgetary expenses to the Currents accounting department.)

Press Freedom Rankings: Getting Better

Quick note: the RSF index can be lacking in specific explanations of why some countries have shot up in their rankings. For example, Taiwan rose three places even though its score only increased by one point and the past year saw clear case of political censorship against a state broadcaster. Similarly with Papua New Guinea, which saw its ranking increase by 13 places against a score increase of just over 2 points.

This implies that, in a number of cases, there hasn’t been much of an improvement in conditions per se, but because of an overall cratering of press freedoms globally, their standings have been pushed up by default.

Taiwan has done a solid job at promoting itself as Asia’s equivalent of the Gaulish village from Asterix and Obelix, standing as a bastion of free speech in a press freedom desert. This has some truth to it: government interference in the media is pretty rare, and the situation in Taiwan looks great compared to neighbours like China; this year, Taiwan moved up three spots for a ranking of 24th place.

But it hasn’t all been a bed of roses. Last year, while covering the US presidential election results, state broadcaster TaiwanPlus was pressured by the Kuomintang (KMT), the main opposition party, to remove a TV news report which referred to Donald Trump as a ‘convicted felon’ (their reasoning for this being that it was ‘inappropriate and biased’, despite the statement being factually accurate); the channel complied with the request and the report was taken down.

I used to work for TaiwanPlus, so this is truly disheartening (and incredibly annoying) to hear, especially after being assured that the channel would maintain editorial independence from political influence.

Generally speaking, though, it seems Taiwan did enough to warrant a rise in the RSF rankings, alongside countries which saw sharp increases: Papua New Guinea, Malaysia and Brunei.

Papua New Guinea climbed up the rankings to 78th this year, after steeply dropping to 91st place in 2024. While there has been a solid base for press freedom, as the RSF report signals: “Reporters are constrained by the interests of the corporations”

Journalists are faced with intimidation, direct threats, censorship, lawsuits and bribery attempts, making it a dangerous profession.

Malaysia surged to 88th place, up from 107 last year and moving out of the ‘difficult’ category to the slightly improved ‘problematic’ section. Brunei also had a strong showing, shooting up 20 places to 97th place, despite RSF saying that “Press freedom is virtually non-existent in the sultanate of Brunei”.

That said, even on face value alone it’s encouraging to see the Philippines gradually moving away the era of former president and current guest of the International Criminal Court, Rodrigo Duterte, whose rule from 2016 to 2022 saw media freedoms severely repressed. This year, the Philippines bagged its best ranking in more than two decades, moving up to 116th place from 134 last year — something even President Ferdinand ‘Bongbong’ Marcos Jr. noted as a cause for celebration.

Press Freedom Rankings: Gimme Shelter

Taiwan often takes the spotlight for having the best press freedom ranking in Asia, though this does a disservice to Timor-Leste — a young country that has been holding it’s own since independence in 1999 (even reaching the rank of 10th place on the RSF index in 2023). Slightly less so much this year, though, as their ranking fell to 39th place (down from 20th last year). This was in part due to the unusual arrest of a journalist and a 2014 media law which “is a permanent threat hanging over journalists and encourages self-censorship”.

It’s disappointing to see Nepal dip in the rankings, too, falling from 74th to 90th place. A country with a vibrant media scene that’s been growing since 2008, the authorities have recently been criticised for dragging their heels on investigations into the deaths of two journalists: television journalist Suresh Rajak, who died in a building fire while covering a pro-monarchy protest in March, and investigative reporter Suresh Bhul, who was beaten to death by a mob in November last year. So far, no one has been charged in connection with either death.

In Indonesia, fresh off the back of electing Prabowo Subianto (a former army general who’s faced very credible accusations of committing warcrimes) as president, the press freedom ranking falling 16 places to 127 (down from 111 in 2024, and it’s lowest ranking since 2016). As the RSF report notes, the sheer size, scale and diversity of Indonesian society makes “respect for press freedom a daily battle” at the best of times. This combined with the election of Prabowo — who had strong links to former Indonesian dictator Suharto — makes the country highly susceptible to further deteriorations in its press freedoms.

In Hong Kong, the years since the introduction of the Beijing-imposed National Security Act have seen press freedoms continue to backslide, this time reaching an RSF ranking of 140 (five places down from last year). After boasting a flourishing media scene for decades following the British handover in 1997, the Chinese Communist Party clamped down on free speech and civil liberties in Hong Kong following pro-democracy protests in 2021, causing Hong Kong’s ranking to nose-dive 68 places the following year. Since then, journalists have been jailed, newsrooms raided and shuttered, and previously respected media outlets struggle with editorial independence and an ever-looming threat of state retaliation for speaking out against China.

Meanwhile, Cambodia is also on a downward trend, dropping 10 places from last year to 161. It’s been sad to see how former prime minster Hun Sen “launched a ruthless war against the media” in 2017 — resulting in the closure of a number of independent groups and most remaining media outlets echoing the government’s talking points — which has continued after his son, Hun Manet, became prime minister in 2023.

Press Freedom Rankings: SNAFU

Getting into the lowest section was always going to be pretty depressing, and this year was no different.

Myanmar has continued to see worsening civil liberties since the 2021 military coup which overthrew the democratically elected government, resulting in a brutal and chaotic civil war. The country’s RSF ranking has risen from an all-time low of 176 in 2022, rising two places to 169 this year. Going forward, more external factors risk crippling many of the media organisations tasked with covering Myanmar — a number of media organisations which cover Myanmar were heavily (in some cases almost entirely) reliant on USAID funding that has since been halted. (For more on this, check out my article from two months ago on how cutting USAID has affected places in the Asia-Pacific.)

When it comes to which country will bottom out on the Index, it usually comes down to a competition between North Korea and Eritrea, with China hovering around the periphery. This time, the dubious honour goes again to Eritrea, the coastal African nation ranked 180 out of 180 countries for the second year running. (I’m not sure what a place has to do to be worse at press freedom than North Korea…) After moving up to 172 in 2024, China — the world’s biggest jailer of journalists — fell back to 178th place this year, followed by North Korea, which dropped from 177 last year to 179. Predictably, this tracks with their previous rankings, and there isn’t much likelihood of improvement anytime soon.

Additional mentions

There have been a few instances where the RSF ranking and reality on the ground seem particularly off-kilter.

Press freedom in Mongolia has seen a gradual decline over the past few years, dropping from 68th place in 2021 to 102nd in 2025. Though the country rose seven places from its 2024 ranking, clampdowns on the press have occurred over the last year, such as the imprisonment of journalist Unurtsetseg Naran, editor-in-chief of the news website Zarig.mn, and a police raid on independent media outlet, Noorog Creative Studio.

Further south, Laos rose three places to 150. While this continues its upward trend since 2021, the one-party communist state has a history of clamping down on free speech, where bloggers and journalists have been detained and activists have been disappeared. As stated in the RSF report: “the state exerts complete control over the media, is an information ‘black hole’ from which little reliable information emerges”.

As such, there’s a particularly embarrassing placement for India (the “world’s largest democracy”) to find itself in — even after rising eight places to 151, India is one place behind Laos. The RSF report is quick to position the blame for this in larger part on the government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi, which has worked to curtail press freedoms in India and plunged the media scene there into ‘crisis’.

India’s media has fallen into an “unofficial state of emergency” since Narendra Modi came to power in 2014 and engineered a spectacular rapprochement between his party, the BJP, and the big families dominating the media.

Buckle up, folks

It’s all rather bleak reading, which highlights some of the huge problems the media industry is currently facing.

The lack of traditional funding and insufficient adaptation of business models for the digital age have meant countless news outlets are chronically starved of money and resources. This comes alongside worldwide rise in authoritarianism, with state actors clamping down on media and journalistic freedoms, and global economic pressures and concerns hammering the industry even more.

And the real kicker is that this is likely to get worse.

The Trump administration’s instigation of a trade war and its cuts to programmes like USAID have only come into effect over the last few months, fairly close to the report’s release date. This means that the fallout might not be fully reflected in this year’s report. For example, media groups which focussed on Myanmar were among the worst affected by the USAID funding freeze — it’s likely that the full extent of the damage will unfold through this year and only be included in RSF’s 2026 report.

All in all, I wish I had better news. But I will say that if you want to support independent journalism in the region, then remember to:

You can also help support Myanmar media groups – some of the worst affected by the USAID funding freeze – such as Than Lwin Khet News (Burmese site here, and Facebook page here).