If someone asks you to think about the Rohingya people, what would be the first thing that comes to mind?

Images of despair, and of families crammed into refugee camps? Of a people fleeing the threat of death as their homes — and history — burn?

Either would be understandable. The Rohingya people — denied citizenship under Myanmar’s nationality laws — have been the targets of one of the worst acts of genocide and ethnic cleansing to occur in the 21st century. And, as happens, the media coverage only ever crops up when moments of devastation occur.

But in addition to physical violence, one aspect of the genocide of the Rohingya is cultural cleansing — a coordinated effort by the state to erase the history of the Rohingya people in Myanmar. In recent years, misinformation and disinformation campaigns have been prolific in their spread across the country, reinforcing a narrative that the Rohingya are intruders who only recently migrated across the border, and were never proper citizens.

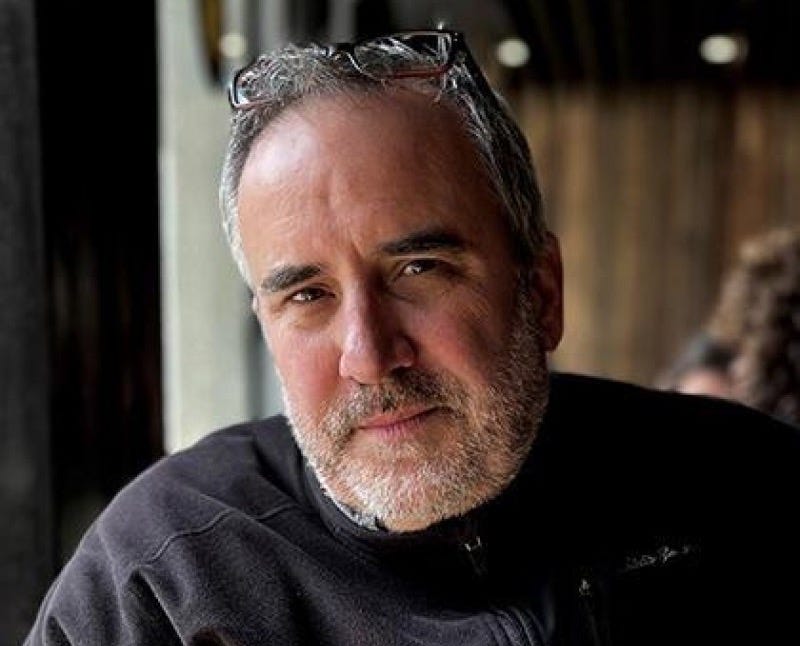

“I think that part of genocide which isn’t talked about very often and isn’t recognised very much, is who people are as a community — about their history, about their heritage, about their culture,” says Greg Constantine, a photographer who’s been documenting the Rohingya people and their stories for around 20 years.

“One of the things that’s been done — very methodically by the Burmese government over all these decades — is to do everything it can to basically erase the history and the acknowledgement of the Rohingya community being a people from Burma, who have contributed to Burma, and who have participated in the development of that country over all those decades.”

Once upon a time

Greg, who’s originally from the US, alludes to a major shift in his life around his late-20s/early-30s, whereupon a brief dalliance with writing convinced him that photography was his path to artistic expression. He started documenting stateless peoples in the mid-2000s, traveling to various countries around the world. The Rohingya were among the first he covered in his series in 2006.

A bit over 10 years later in 2017, the Myanmar military ramped up its efforts to remove the Rohingya from state territory. The genocide perpetrated by state actors resulted in tens of thousands of deaths and millions displaced, many of whom fled across the border to Bangladesh, primarily to Cox’s Bazaar.

It was around this time that the world woke up to the persecution the Rohingya had been facing. Coverage of their plight made headlines around the world, and stories of the horrors they’d experienced were in fast supply. Greg, who’d been covering the largely overlooked Rohingya community, now had a front row seat to a global story.

Greg’s documentation of the persecution of the Rohingya was exhibited in various places — including the National Holocaust Museum in Washington, DC. But after the DC exhibition, he says he took some time to reflect on the narrative surrounding the Rohingya — and how to disrupt that.

The result was Ek Khaale, a Rohingya expression meaning ‘once upon a time’. It could be considered the culmination of Greg’s work attempting to push back against itself, and other narratives that portray the Rohingya solely as victims.

“I wanted to do something different that would challenge my own body of work,” he says. “For me, if I’m going to continue to keep working on this story, what could I do that’s completely different from what I’ve done before? Because I could go into Bangladesh, and keep making pictures of this community of being the victims — of suffering, the desperation — of being all these labels that’ve been imposed upon them.

“I came to the decision that [the] work wasn’t doing enough to disrupt the trajectory of the narrative that’s been told of the Rohingya all these years. And I felt like, okay, if I want to do something different, I need to do something that’ll disrupt this; it’s going to disrupt not only me, as a photographer and the work I produce, but that same old narrative that everyone keeps pushing about this community.”

Changing the narrative

In this episode of Currents, I speak with Greg about his work documenting stateless peoples, the Rohingya, the current situation in Myanmar, and how he hopes Ek Khaale can shift perspectives.

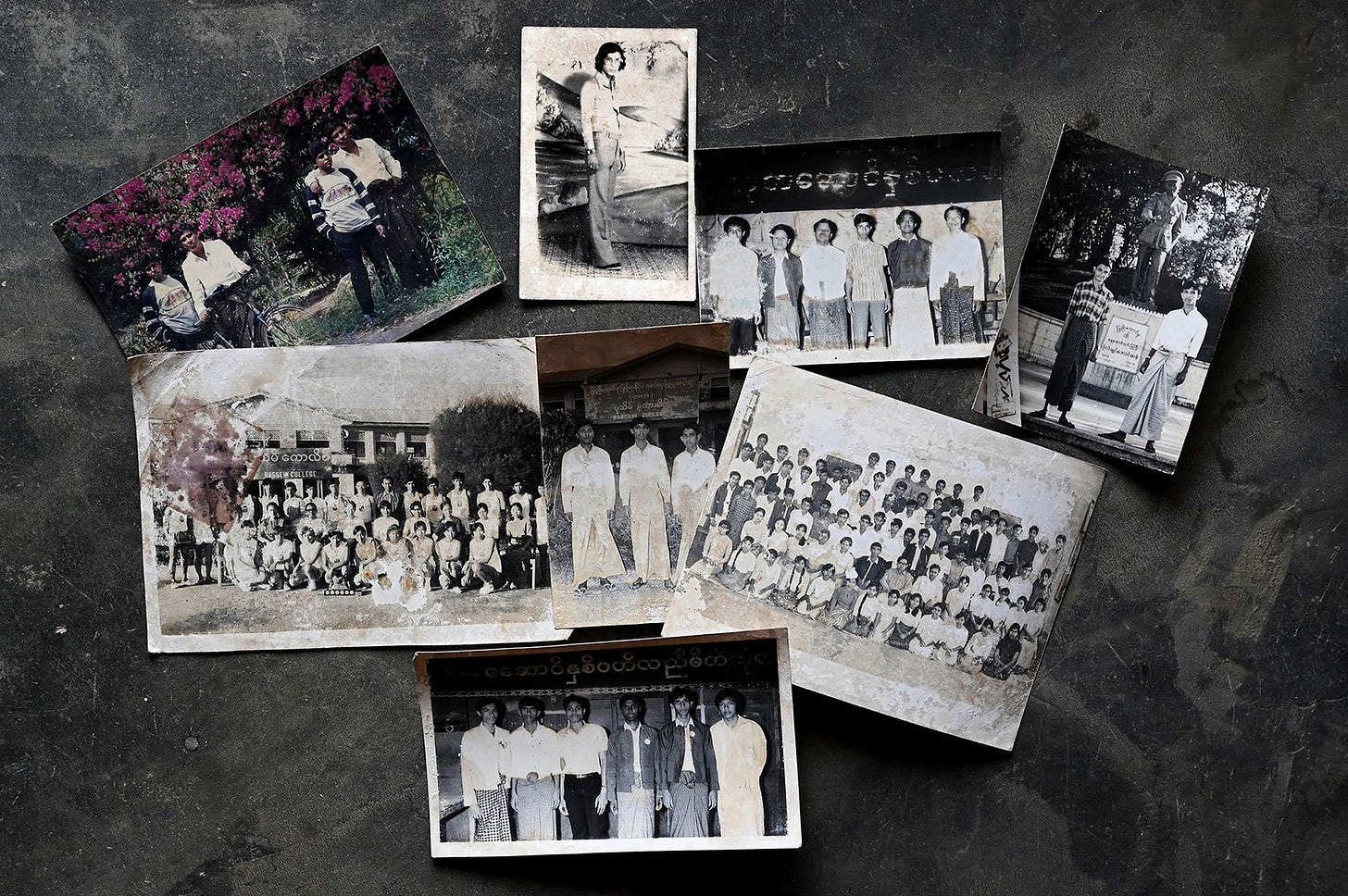

Ek Khaale is currently on display in Bangladesh, following on from its maiden exhibition in northern Thailand last month. The project, which has been running for around four years, is the result of a collaborative effort that wouldn’t have been possible without the contributions of the Rohingya people. Greg talks passionately about how continually surprised and moved he has been by the extent of the salvaged historical records — preserved despite ongoing persecution and repeated displacement.

“It’s a privilege to be part of that process,” he says.

“When you really think about it, this project is not just about presenting a whole new visual portrait of the Rohingya community [...] it’s a vehicle of resistance. Every single contribution — from one singular photograph, to a document, to a whole portfolio of documents by a Rohingya individual or a Rohingya family — the fact is, that contribution is a resistance against the labels that have been imposed upon them. It’s a resistance against the narrative that the Burmese authorities have spread over all these years. And it’s an act of resistance against the visual identity that has been created, that represents them, by other people.”

Ek Khaale will be on display at BRAC University’s Exhibition Hall in Dhaka, Bangladesh from August 17-28 . You can also view the visual restoration and story of the Rohingya on the Ek Khaale website.