After talking for several minutes about his nine-month confinement in the ‘special section’ of Myanmar’s infamous Insein prison, Sonny Swe takes a second to reflect.

“[Being in there is] probably the lowest point of a human being,” he says. “The animals… sometimes you feel like the dogs and the cats of the [prison] staff, they live better than us because they treat them as their family members. But they treated us like animals.

“This is the place you don’t want to be,” he adds nonchalantly.

Sonny, a Burmese magazine publisher and co-founder of newspaper The Myanmar Times, was in his mid-30s when he was arrested in 2004. After months of being imprisoned without charge, he was eventually sentenced under Printing Act 20 law — a vaguely worded statue that could be applied to almost anyone the previous junta government chose to target.

However, he believes the real reason he was targeted was far closer to home: Sonny’s father was a senior Air Force intelligence officer who’d been arrested a month prior amid a purge of intelligence officials during a split in the military. Sonny was eventually sentenced to 14 years.

Upon entering prison, Sonny was placed in solitary confinement in a cell six-by-10 feet wide, with a dirt floor and only a wooden pallet for a bed. Insects and scorpions worked their way out of the ground at night (they considered the cell their nest, Sonny said), while the guards flashed torch-lights in his eyes and bashed on the bars to ensure that prisoners couldn’t sleep for more than a few minutes at a time. Even trying to drink water from a bucket placed near the cell door involved having to contort a cup that was bigger than the width of the bars.

Sonny endured prison life across five penitentiaries for the best part of a decade. Following democratic reforms in 2011, during which Myanmar transitioned from a military government to a civilian one, he was finally freed in 2013.

The first thing he did upon release was to return to his newsroom.

For this edition of Currents, I sat down with Sonny to discuss his experiences growing up and working in Myanmar under the previous junta, how he survived harrowing conditions in some of the world’s worst prisons, and his reaction to the devastating earthquake which hit the country earlier this year.

Four years of death and destruction

In February 2021, the Burmese military staged a coup which overthrew the civilian government in Myanmar. The move sparked mass protests, which the authorities clamped down on quickly and brutally.

Sonny fled Myanmar soon after, out of fear of being targeted by the authorities for a second time. He now lives in Chiang Mai, the largest city in northern Thailand located around 250 kilometres from his home country’s border, which has become something of a haven for Burmese exiles. He’s since opened a co-working space and modest Burmese restaurant, both as much reminders of home as they are business ventures.

The number of problems and hurdles facing those who fled Myanmar have only increased. Four years on from the coup, Myanmar is engulfed in a brutal civil war where armed groups hold sway over around half of the country and the military struggles to maintain control. As the junta loses both ground and troops (whether as casualties or defections), its leaders have resorted to increasingly desperate measures, such as introducing mandatory conscription for all men aged between 18 and 35 and all women between the ages of 18 and 27 — a move that caused even more people to attempt to flee the country.

For those who have already fled, there are constant struggles with their immigration or visa statuses. Many are trapped in a state of limbo, unable to renew their passports due to risk of arrest or repatriation should they attempt to do so in Myanmar embassies or consulates.

The desperation of the situation was made even worse earlier this year, after an earthquake with a magnitude of between 7.7 and 7.9 hit Myanmar in late March. With shockwaves felt as far away as Ho Chi Minh City in southern Vietnam over 1,000 miles away, the quake was the most devastating experienced by Myanmar in almost a century, wrecking buildings and infrastructure in an already beleaguered country.

The March 28th earthquake

Myanmar is no stranger to natural disasters: in 2008, Cyclone Nargis made landfall and is estimated to have caused the deaths of almost 140,000 people, mostly along coastal regions. At the time, the former junta refused to allow much international aid into the country, with some of the more populated areas like Mandalay, the country’s second largest city, and Naypyidaw, the capital and government administrative hub, being far enough away from the brunt of the storm.

This year’s earthquake was different.

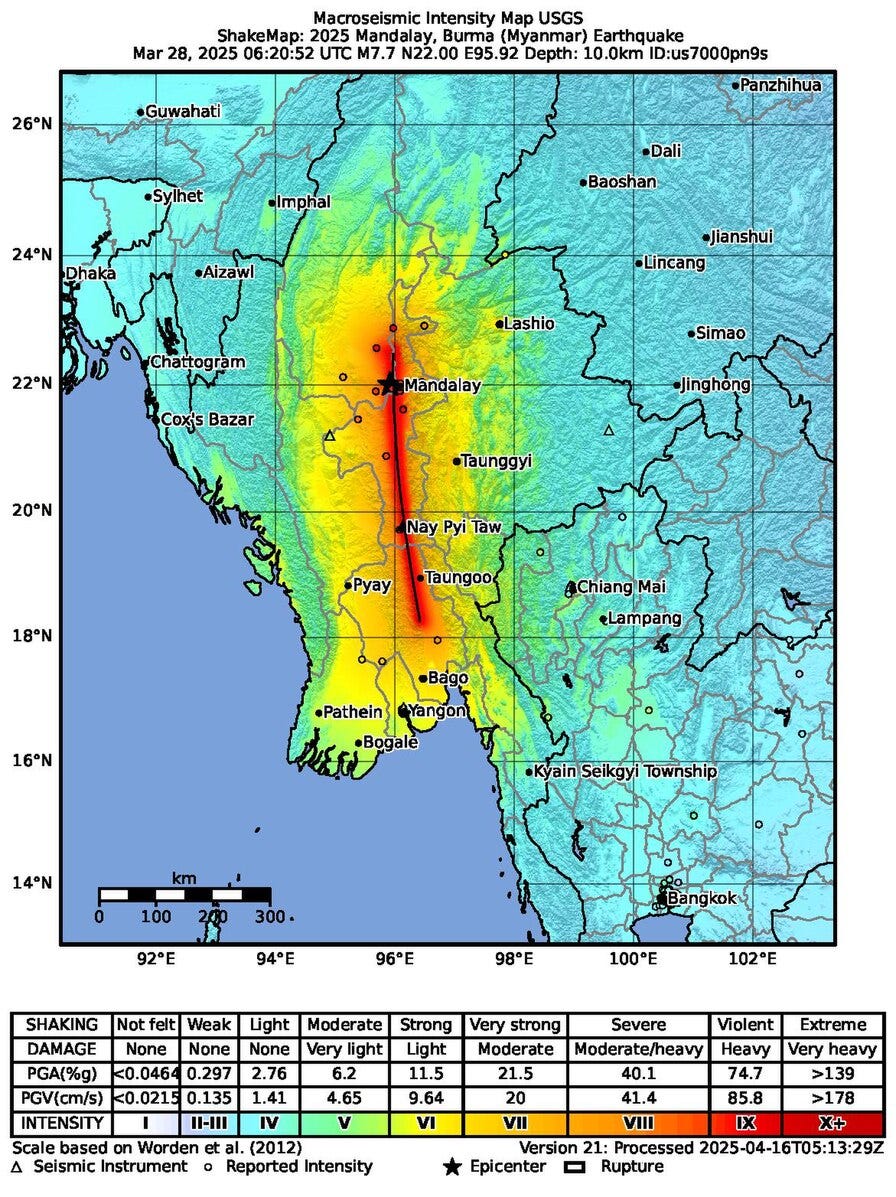

A map from the United States Geological Survey (USGS) shows that the fault-lines run through the middle of the country — tearing through Mandalay and Naypyidaw, stopping a couple of hundred kilometres north of Myanmar’s most populous city, Yangon.

At the time of writing, the official death toll stands at just under 5,500, though estimates from the USGS say that anywhere between 10,000 and 100,000 people could have perished. Upper estimates for the economic costs stand at around $100 billion — far exceeding Myanmar’s GDP of $65 billion.

Through his contacts in the country, Sonny learned that many people are still sleeping outside due to the instability of the buildings and the fear of aftershocks, while the smell of corpses rotting under the rubble remained constant and overpowering. A number of countries and humanitarian organisations have offered aid to Myanmar in the form of money, medical supplies and rescue teams. But the ongoing civil war has hindered relief efforts, and some areas still are struggling with the fallout months later.

The exact number of deaths caused by the earthquake may never be fully known.

Resilience in the face of devastation

This is the first half of a two-part interview with Sonny, focusing on his time in prison and the fallout from the earthquake. In the second part, due to air next week, we discuss the devastation the civil war has wrought in the country, and where Sonny sees it going from here.

This interview was one of the most exhausting I’ve ever conducted, with the details of Sonny’s incarceration, the fallout from the earthquake and the brutality of the civil war adding layer upon harrowing layer of suffering on a country and a people who have already borne so much.

But amid the destruction and despair, there remains a sense of determination and resolve. Sonny’s stories of perseverance and survival are but one example of the strength seen in the Burmese people — as he said during the interview: “The resilience of the Myanmar people is amazing.”