Reasons for supporting or opposing the death penalty vary from person to person — even among abolitionists, some arguments resonate more than others.

That said, there is no denying the jarring, bizarre, and often contradictory nature of state-sanctioned killing.

In cases of the death penalty for murder, the punishment is precisely that which the state insists is morally egregious and forgivable — taking a life. Meanwhile, measures are taken to alleviate the guilt and horror for people tasked with killing, such as putting blanks in some of the guns used in firing squads, using dummy buttons when administering lethal injections, or requiring death row prisoners to pray before altars so their spirits do not return to haunt their executioners.

Then there’s the way prisoners with health conditions are treated.

“There’s this terrible irony that if someone’s unwell, [the state] won’t execute them while they’re unwell,” says Elizabeth Wood, CEO of the Australia-based abolitionist group the Capital Punishment Justice Project (CPJP). “So they [say] ‘okay we’ll delay it; now you’re healthy, now we’ll kill you’.”

A prime example is the case of Nagaenthran K. Dharmalingam, known to friends and family as Nagen, a young Malaysian man who was on death row in Singapore for drug trafficking.

Nagen’s case had already courted controversy and international attention because he was assessed as having an IQ of about 69, as well as ADHD and impaired executive function. Despite this, his execution was scheduled in November 2021, during the middle of the Covid-19 pandemic.

The day before his scheduled date of death, Nagen was brought into court for an appeal hearing.

“The argument that was going to be made by the lawyer in court was that Nagen wasn’t psychologically fit to execute,” says Sara Kowal, Director of Eleos Justice at Monash University’s Law department and Vice-President of CPJP. “There was severe concern about hallucinations he was having and his mental health, and so the argument was that someone not only has to be physically fit to be executed, but mentally fit to execute.”

Shortly after the court went into session, Nagen was ushered out and the hearing was adjourned after it was discovered he had tested positive for Covid, thereby postponing his execution. “If the applicant has been afflicted by Covid-19 […] it’s our view that the execution cannot take place anyway,” Justice Andrew Phang, one of the three appeal judges, said at the time. “I think here, we have to use logic, common sense and humanity,” he added.

“Looking from afar then I thought ‘wow, that’s amazing’, because that really goes to the idea that if you can’t be physically fit to execute then maybe they will also have an appetite that you also have to be tested for psychological fitness, or psychiatric fitness,” says Sara.

The 33-year-old was given a little more time and anti-death penalty activists breathed a sigh of relief, but the reprieve was brief. Nagen made a full recovery and was hanged the following April.

Successes and setbacks

Elizabeth and Sara — both natives of Victoria, the last state to execute someone in Australia — bring up these issues in this edition of the Currents podcast, recorded while they were in Manila to attend a regional conference organised by the Anti-Death Penalty Asia Network (ADPAN). In their time working on numerous cases, the pair are more than familiar with the bittersweet nature of anti-death penalty activism.

In recent years, there have been major setbacks in the abolitionist movement in the Asia-Pacific, such as executions resuming in Myanmar in 2021 after the military took power in a coup, and Singapore ramping up hangings over the past three years.

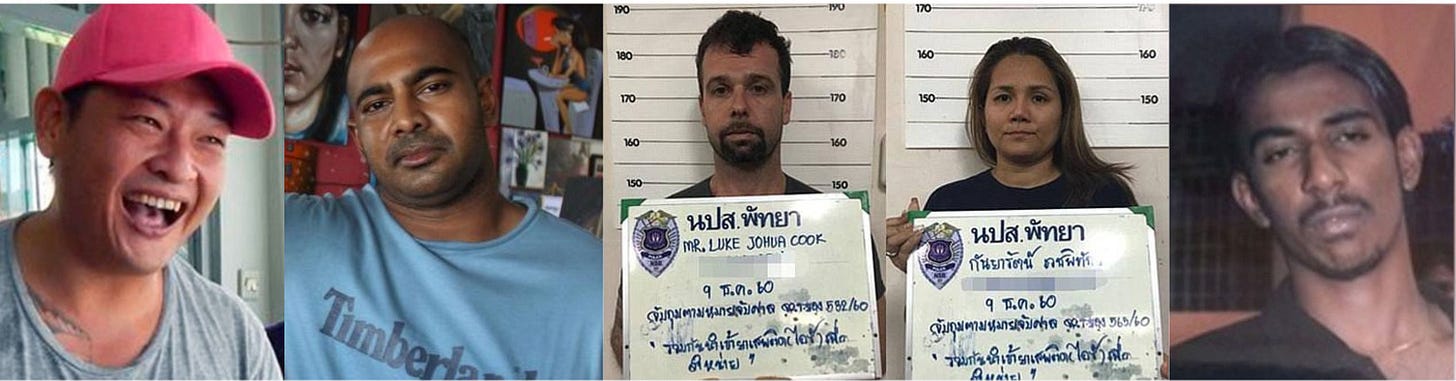

But this is weighed against some significant wins: the Philippines avoiding reintroducing the death penalty in 2017, the release of Australian Luke Cook and his Thai wife Kanyarat Wechapitak, who were acquitted in 2021 after spending four years on death row in Thailand, and Malaysia abolishing its mandatory death penalty in 2023.

More recently, abolitionists celebrated the repatriation of Mary Jane Veloso, a Filipino former domestic worker who was returned to her home country in 2024 after being on death row in Indonesia for 14 years.

The Legacy of the Bali Nine

Throughout the podcast recording, Elizabeth and Sara repeatedly bring up the Bali Nine — a case that eventually pushed the Australian government to make the abolition of capital punishment one of its foreign policy priorities.

In 2006, nine Australian citizens were caught attempting to smuggle drugs through Bali airport in Indonesia. Andrew Chan and Myuran Sukumaran — the two supposed ringleaders — were eventually executed by firing squad about 10 years later, and Tan Duc Thanh Nguyen died of stomach cancer in 2018 while still incarcerated. Between 2018 and 2024, the six remaining members of the group were sent back to Australia, whereupon their life sentences were commuted.

The Bali Nine case struck a particular chord in Australia — not just because their citizens were serving far harsher sentences than they would’ve received at home, but also because of the perceived culpability of the Australian authorities. During the case, it was revealed that the Australian Federal Police (AFP) had tipped off the Indonesian authorities, thereby leading to their arrests, imprisonments, and, in two instances, executions.

Since then, Australia has become one of the most vocal proponents of calling for the end of capital punishment around the world. This gives a group like CPJP an opening to provide much-needed solidarity and support to peers working in retentionist states.

“I think the real benefit is operating under an abolitionist government, and one that has a policy that they actively support the worldwide abolition of the death penalty, means that we’re absolutely safe to work freely, and to support others when they’re facing an authoritarian state or genuine repercussions for their work,” says Elizabeth.

“And we do try to raise awareness in Australia as well, because it can really be forgotten about. It’s not a penalty in Australia, so the constant question is ‘Why do you do this work? We don’t have the death penalty’. It’s still a relevant human rights consideration, and we should all care about states that use this power.”

Coming up over the next week

This is the first of a two-part episode of the Currents podcast with Sara and Elizabeth — tune in next week for the second and concluding part of our discussion.

Also coming next Friday is an interview with Filipino painter and former prisoner, Arturo De Guzman Pangilinan, and his wife, Dolores (better known as Dolly). Art, as he’s known to his friends and family, spent almost 31 years in prison — some of it on death row.

Art took up painting in prison; he’s still adjusting to life as a free man after his release in January, but is committed to contributing to the anti-death penalty movement.