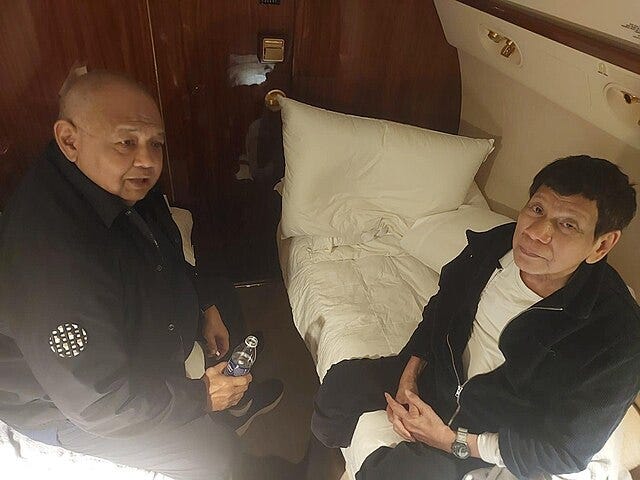

Rodrigo Duterte’s plane touched down in Ninoy Aquino International Airport in Manila on the morning of March 11. Hours later, he was under arrest and on a flight to Brussels to face a pre-trial hearing at the International Criminal Court (ICC) in The Hague.

The series of events leading to his arrest for crimes against humanity were, by all accounts, remarkably uneventful. Duterte was informed of the charges against him by Philippine police officers, and, after some toing and froing, was led to another plane on which he was jetted off towards an uncertain fate.

This acquiescence stood in sharp contrast with the combative and bellicose persona the former president of the Philippines had nurtured for decades — one that had shocked people around the world and spurred on a campaign of fear and violence as part of a brutal war on drugs.

‘An attack directed against a civilian population’

From the moment Duterte threw his hat into the ring for the presidency, it was obvious he was adept at courting controversy and polarising opinions.

In the Philippines, he had already established his image as the tough, no-nonsense mayor of Davao City, waging a city-wide war against the illicit drug trade. Many Davao residents credited ‘Duterte Harry’, as he had become known, with cleaning up their city and transforming it into one of the safest in the country. At the same time, human rights groups regularly reported ties between the mayor’s office, the police and the ‘Davao Death Squad’ — a group believed to have been responsible for over 1,400 vigilante killings of alleged drug dealers and criminals in the city since 1998. (This was confirmed by Duterte himself during an official government investigation last year, where he said he kept a death squad made up of ‘gangsters’ whom he told “kill this person, because if you do not, I will kill you now”.)

Duterte made headlines for comments that brushed off acts of extreme violence. He caused international outrage in 2016 after it emerged that he had previously made light of the rape and murder of an Australian missionary during a Davao prison riot in 1989. Duterte, then still a presidential candidate, apologised, but made another rape joke in a speech to military personnel a year later; this time as president.

After taking office in 2016 following a landslide victory, his presidency essentially involved an escalation of the methods established in Davao — now on a national scale. Duterte weaponised the police and vigilante gangs, with death squads given carte blanche to carry out campaigns of violence against those they classified as criminals or drug peddlers. According to a 2020 UN report on the extrajudicial killings, the perpetrators were given ‘near impunity’.

All the while, Duterte doubled-down on his rhetoric encouraging violence: “If you know of any addicts, go ahead and kill them yourself as getting their parents to do it would be too painful”, he told Filipinos hours after being sworn into office. He threatened drug addicts by saying “My order is shoot to kill you. I don’t care about human rights, you better believe me.” In 2018, he told soldiers to shoot women communist insurgents “in the vagina”, adding “if there are no vaginas [the woman] would be useless”.

Activists speak of a culture of fear that spread throughout the Philippines during this time. People who were ‘red-tagged’ — being labelled as communists or terrorists — became fair game for targeting. Without any supporting evidence, almost anyone could be accused of being a ‘pusher’ or a political subversive (and therefore implicitly aligned with drug dealers) on social media, and their lives would immediately be at risk.

The exact number of deaths from this period is unknown. Officially, the Philippine government estimates around 6,000 people were killed, while human rights organisations and the ICC place the number at well over 30,000. The 2020 UN report cited earlier found that at least 73 children were killed in the drug war, the youngest being five months old.

In a statement confirming Duterte’s arrest, the ICC wasted no time linking the former president with death squads operating in the country, describing protocol during his premiership as:

[An] attack directed against a civilian population pursuant to an organisational policy while Mr Duterte was the head of the Davao Death Squad (DDS), and pursuant to a State policy while he was the President of the Philippines.

War on drugs, war on dissent

While waging its drug war the Duterte regime also clamped down on dissent and political opposition, targeting activists, lawyers, journalists and politicians. Many were threatened or imprisoned. A number were killed. Those who endured these years still carry the trauma of their time living on the precipice.

But despite the outcry from human rights groups, international condemnation and the clear spread of violence across the nation, Duterte enjoyed high levels of support in the Philippines and maintained significant influence, even after his time in office ended in 2022. For many Filipinos, the former president is still considered a hero: a crusader against injustice and the righter of societal wrongs.

This week, however, Duterte celebrated his 80th birthday in detention — something he had previously said would never happen while he was still alive. His indictment came as a huge shock to both his supporters and detractors, many of whom believed he was virtually untouchable; after the news broke, numerous demonstrations were organised both in support of and to protest the ICC.

Many have since questioned the process and timing of his arrest, and rumours abound that the move was politically motivated. While the Philippines is not an ICC member, the official line from the authorities is that Duterte’s arrest was made due to the police’s cooperation with Interpol — who were acting in accordance with the ICC warrant. People have speculated that this has much to do with a reported falling out between the Duterte family and the current president, Ferdinand ‘Bongbong’ Marcos Jr.

‘One death is one death too many’

Pundits and analysts will continue to theorise and speculate on the political manoeuvrings going on behind the scenes. For Currents, though, I would prefer to focus on the human cost and experiences of Duterte’s war on drugs.

I spoke to Cathy Alvarez, a human rights lawyer who worked with StreetLawPH, an organisation focused on access to justice and drug policy, and Karen Gomez-Dumpit, the former Commissioner at the Philippines’ Commission on Human Rights.

Both Cathy and Karen fought hard to defend human rights throughout the Duterte administration and were regularly exposed to traumatic cases of violence and abuse. As Cathy remarked in our interview when asked about the death toll: “My position is that one death is one death too many”. For them, Duterte’s arrest is a moment of huge relief and catharsis… but not without anxiety over what might happen next.

This is the first in a two-part episode on the arrest of the former Philippines president. You can listen to the second half of my conversation with Cathy and Karen via the link below: